line———

Anxiety as script, shape, and destiny

I’m able to pursue creative work like this thanks to your paid support. Thank you!

Dr. Brady slid a blank sheet of printer paper over to me from across the table. I loved printer paper. I ate through reams of it at home. I’d open a drawer in my dad’s office—O, the crisp, clean scent of wood pulp!—remove a fat stack and populate the white space with dragons, dinosaurs, and birds of my own invention. Cool things. No smiling lady in a MOM dress, no boxy house with a pointy roof, no sun wearing sunglasses, those favorite subjects of my peers (total non-talents).

“Draw me something,” Dr. Brady said. Dr. Brady looked like a crane, if I recall. She was tall and thin and silver and discerned my wrong/bad answers from my right/good ones with a little jerk of her beak.

“Okay,” I brightened, eager to do something I was good at. I hadn’t been so good at answering her questions about my family, “friends,” or media diet. Most of these answers Dr. Brady had sifted into the WRONG! category, which was on her left/my right. “What should I draw?”

“Whatever you want.”

There’s that horror movie trope. You know the one? It pops up in films with an invisible monster: The haunted child draws the entity that they alone can see.

I found, and continue to find, great solace in lines. But especially so in childhood. The world was unclear, and I was afraid. I was small and confused and afraid. I trembled. I cried. Lines were allies in my struggle against unclarity. I drew a lot. I was good at it.

“Look! He’s good!” my mom said, holding up the Etch A Sketch she’d bought me for Christmas. I was five. I’d drawn a gun (as in, illustrated). Firearms were an unusual theme for me. I wasn’t a school shooter (I wasn’t masculine enough). Knowing me, I’d Etched some shape, then let that shape dictate itself into existence. It might have looked like this:

Draw: move, pull, create, extract, elicit, inhale, contract, come, go, delineate. I had pretty much everything I’d ever need in there.

When I wasn’t drawing, I was reading. Sentences are lines too. I’d like to say I read so much because I had a thirst for knowledge or a big imagination, but I don’t think that’s quite what was going on. I read indiscriminately. I grabbed at books in the school library with the attention to preference one might expect of a starving tiger set loose in a pet store.

I read good books and bad books. I read books for adults and books for toddlers. I read fiction and nonfiction. I read biographies, stale accounts of obscure wars, ecofeminist sci-fi, diaries recounting the daily ordinaries of polio, glorified pamphlets stuffed with colorful fun facts about animals (the Komodo dragon has a third eye!), and that’s not even including my forays into the robust genre of dogs solving crimes.

Subject matter was irrelevant. What mattered was that a book was a complete world with a set beginning and end. If I didn’t understand something, I could go back. If I disliked it, I could leave. If I liked it, I could return again and again. I liked maneuvering my brain back and forth along the track: letters—words—sentences—paragraphs—chapters—book.

Drawing. Reading. Ink. Lines. Lines dictate and define. The lines of a letter conduct mind-sounds. Do so here: the rounded elegance of a; the pleasant, buzzing, downward drill of teeth to lower lip to go vvvvvv, a letter that looks like itself, a diving, winged insect with a stinger. This is to say I preferred inked worlds to “the real one,” where absolutely anything could happen at any time. If I wasn’t reading or drawing, I tended to overthink things and mess up. I messed up a lot.

I didn’t know how to communicate with my classmates. I’d repeat lines from TV, movies, or books. This didn’t work out so well as Three’s Company only covers so many real-world scenarios, most of them inapplicable to life in a Catholic elementary school. Plus, people, even or especially kids, can sort of tell when you’re being phony with them. But I felt I needed my lines. I clung to them like I clung to the side of the pool (I, of course, couldn’t swim). Without them, I panicked. Thrashed. Flailed.

This put me in a misery loop: My classmates made me anxious—my anxiety made interacting with my classmates difficult—I overthought, and thus fucked up, my interactions with my classmates—these botched interactions did not endear me to my classmates—you can only score so many soccer goals against your own team before they decide they don’t much care for you—my classmates decided they didn’t much care for me—I became even more anxious in my interactions with my classmates because I’d dug myself into a hole—more anxiety=more overthinking=more fucking up—more fucking up=digging an even deeper hole=more anxiety—I became resentful and even hostile to my classmates because I felt totally hopeless, in the hole—being openly resentful and hostile imperils the project of endearment considerably—in my defense, Matthew’s macaroni mosaic, you’d have agreed with me, was entirely unoriginal—I became the kid nobody liked—I saw myself as the kid nobody liked—I got in the habit of being disliked—we are our habits—what we regularly do becomes who we are and who we are is how we see the world and how we see the world is etc, etc—

My parents didn’t know what was wrong with me. I was always crying and faking being sick so I could be sent home. I melted into the role of “sick kid.” I’d actually throw up and everything. I became familiar with the squeaky plastic of the recovery couch (itself the color of jaundice) in the nurse’s office. I’d lie on my side, fire in my throat, eyes treading and retreading the laminated copy of the Lord’s Prayer on the wall hanging centimeters from my face: Our Father, Who Art in Heaven…

The pursuit to name what was wrong with me led to several waiting rooms with bead mazes in them. Perhaps you’re familiar: painted wooden beads that can be moved along wire pathways. Weak competition to a PlayStation, but I loved these things. The waiting rooms held more clues than the doctors on the other side of them. An X-ray revealed nothing except the existence (and unfortunately the taste) of barium milkshakes. In an insult to my intelligence the doctor billed it as “strawberry-flavored.” He diagnosed me as overweight and sent me on my way.

I became what’s known as a problem child. This sucked because a) unlike having a rare disease, being a problem child doesn’t come with a community nor does it engender sympathy, and b) my grades were excellent so I was doing the work of a well-adjusted child for I guess no reason and c) to be a problem child is to be a powerless witness to your own behavior, to understand, to totally get, why no one likes you. The problem child does not like himself.

I was trapped.

“There’s someone I want you to see,” my mom told me one day.

“Who?”

She pitched Dr. Brady as someone interested in my “advanced reading level.” I received this as fantastic news since I’d been coping with my misery by convincing myself that no one liked me because I was smarter than them and not because I was actively antagonizing them like the Phantom of the Opera (we tell ourselves stories in order to live). Maybe this lady would be the first person to understand where I was coming from.

Anxiety—Latin: Angor—Its verb, Ango: “to constrict”—A cognate, angustus: “narrow”—Angst.

In A history of anxiety: from Hippocrates to DSM, Marc-Antoine Crocq, who is French and a doctor, notes and finds it “interesting” that a relationship between narrowness and anxiety is found both in the Latin roots of the word and in Biblical Hebrew. Specifically, it’s in the story of Job. You’re probably familiar: God, bored, accepts a bet with Satan. God wagers that Job will remain faithful no matter the punishments that Satan heaps upon him.

“Just go totally bananas,” God says to Satan, of the punishments.

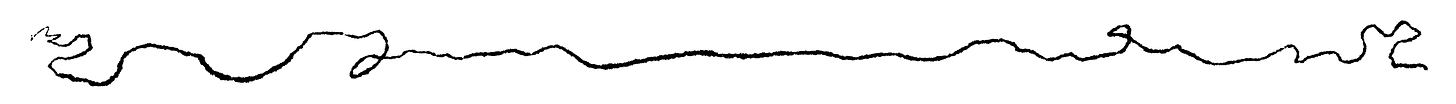

Satan does a number on Job: All ten of Job’s children die (that’s a lot)—Job gets boils on his face—his neighbors, sympathetic at first, become certain he’s done something wicked to deserve all this, for God would certainly not punish an innocent so harshly (HAHA someone hasn’t met God!)—children begin to mock Job—childless, ugly, unpopular Job expresses to the sky “the narrowness” of his spirit, for he was “surrounded on all sides” with distress and the sorrows of death—Job proclaims that he is “like one pent up in a narrow place, in a close confinement”—and indeed he is, that is exactly his situation; God (Fate) has whittled Job’s life away to a thin, brutal track: bad thing—& then bad thing—& then bad thing—

This is a story in a book.

The image in my brain was of a jet-black horsehair worm. I didn’t know what a horsehair worm was at the time. It’s only now as an adult that I can Darwin it out as a horsehair worm. It was long and thin and alive. I know I pictured it this way. I remember the daydream.

The daydream was consistent: A surgeon wearing blue latex gloves would make an incision in my skull and delicately pull the thing out with tweezers. The writhing vermicular string would be laid on a lightly bloodied napkin on a silver tray where I and everyone else could see it (Sister Tiolinda and a smattering of my classmates were present at this ectomy). I’d wake up to find it, the thing, outside of me—real after all.

It was real! Thank God, none of that had been me. How sweet the relief, the absolution, the easy transfer of blame off of me and onto the undulating thing on the silver tray. I was lucid and reborn. Everyone apologized to me and agreed it was an awful thing I’d been hosting in my head. I was brave, even, for managing as well as I had. Yay!

That’s not where the daydream ended. What happened next has been the subject of curiosity for me as an adult. The doctor would inform me that the string couldn’t be killed. It would always find its way back to me. It could however be cut up. Its pieces would have to be distributed. He’d cut it up, place the segments in little capsules, and task me with distributing them to my classmates. I would suffer some, but not as much. My classmates would suffer a bit, but they’d finally understand me.

Daydreams can take whatever shape the dreamer fancies. I could have dreamt of simply being free from my condition, but I didn’t. Theories abound, including these:

I was evil!

What a lonely, unliked child wants more than anything is to be understood. He wants this more, even, than he wants to stop hurting.

The line, like a line in a book, had a desire to communicate.

I see an eerie echo of my adult life and career.

This raises questions as to who or what the author is.

If I reach the end of this sidewalk in an even number of steps—then my mom’s tumor will be benign—but if I don’t, she’ll call me in an hour—her voice will be low and serious and sad.

If I pause the song playing on my phone at the very second that it ends, at precisely 2:26—then I’ll get the job—but if I don’t, if another song starts playing before I hit “pause,” I won’t hear back—an email received weeks later will open with, ‘Thank you so much for your interest! Unfortunately…”

Ritual plays a major role in the life of an anxious person. The poor creature is ruled by a fate obvious only to themselves. My friends with anxiety have privately disclosed all sorts of strange rites, and then only after I offered some of my own. What is ritual? A repeated, structured sequence of actions, words, or behaviors meant to alter the internal or external state of an individual, group, or environment.

Prayer is an example. Prayer names a want. Prayer also names a fate, an arbiter, God. Prayer draws a direct line between the person and Fate, between the want and the omnipotent being that can satisfy it. The notion that this line exists, that it really, truly exists, is precisely that: a notion, a thought, a story.

We need this story to be real, though. We very much need it to be real. If it’s not, well, let’s not even think about that. What other technology have we against oblivion? Let’s keep our focus on making it real. For something to be real, we need to be able to see it. Luckily, we’ve plenty of tools to that end: language, breath, song, daggers, blood, pain, sweat, prayer—fingers working their way down a rosary.

Might anxiety, in its compulsive rituals, be prayer?

Line is an edge. Line is a successive series of events. A line in a script is destiny to an actor’s mouth. To cross a line is to go too far and enter wild territory. Blur a line, lose a friend. Line is a powerful thing. The presence of a line on a plane can cleave infinity in half. Here’s a line for a chess game, where white utilized the Nimzo-Indian, Botvinnik System:

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e3 O-O 5.Bd3 d5 6.a3 Bxc3+ 7.bxc3 c5 8.cxd5 exd5 9.f3 b6 10.Ne2 Ba6 11.O-O Re8 12.Ng3 Bxd3 13.Qxd3 Nc6 14.Bb2 Rc8 15.Rad1 cxd4 16.cxd4 Na5 17.e4 Qc7 18.e5 Qc2 19.Qxc2 Rxc2 20.exf6 Rxb2 21.Rfe1 Re6 22.Re5 g6 23.Rxd5 Rxf6 24.Rd8+ Kg7 25.d5 Nc4 26.Ne4 Rf5 27.Rd3 Ne5 28.Rd1 Rxf3 29.gxf3 Nxf3+

It ended in a draw!

Such are the rantings and ravings of the conspiracy theorist holding a cardboard sign in my amygdala. His latest thing is that this “line” business snakes all the way to the top: Think about it, doofus. My line of work. My family line. The G line terminates at Court Square. Lineus is a genus of nemertine worms. “The first step in wisdom is to know the things themselves,” said, yep, Carl Linnaeus! You think all this is a coincidence? You stupid?

He can be convincing.

Say, buddy, you ever notice how you’re always whittling? Biting your lips, digging into your flesh with your fingernails, balling up your fists, clubbing up your toes and grinding them into the floor? You recall, I’m sure, that dinner party where you were trying so adamantly to chew through your lower lip that you bled? Think about who’s in control here. Suppose these urges got their way. Say they weren’t impeded by flesh and nerves. What shape would it leave you in? Care to describe that shape? What does a hunk of wood look like when it's whittled down to nearly nothing? A toothpick, I reckon. You’d be a thin, narrow…

He narrows his eyes at me and backs away slowly.

I just realized somethin’...

Unlike other states of agony, anxiety is remarkably landscapeless. I can see the world through the lens of depression: the world is coated in the sickly pall of nearly-rotten fruit; it would taste like mush in my mouth, so I don’t eat of it. This unwelcome asceticism does reveal certain appreciable truths. I can see the world through physical illness. Woolf, on having the flu: "how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to light.”

Anxiety, meanwhile, carves the world away until all that remains is a thin, black fate—then—& then—& then—& then: I will fail to finish writing my book—& then years will go by—& then I’ll realize too late that I’m old and out of time—& then this life of mine will have been wasted—& then I’ll die, unexpressed.

What’s being described here is less of a state—sadness and anger, for example, are states, with state capitals, appreciable architecture, flora, fauna, and topography—and more of an act. Disentangle anxiety from thickly forested fear, and anxiety has more to do with doing, is more of a response to fear. I tested this. When I found myself drawing up one of those &—&—&—&’s, I asked: is this something I’m feeling, or something I’m doing?I found that what I was feeling was fear and what I was doing was a crude attempt at giving that fear a shape, borders, lines.

In the horror movie trope, the child draws an entity only they can see. The drawing is scary to us because it implies something unseen. But to the haunted child, the act may very well be soothing. It’s why the monster in the movie is at its scariest in Act I, before it discloses that it’s an actor in a costume, or that it was meticulously rendered on a computer. When things take on a shape, they can be understood.

I wanted to impress Dr. Brady with my drawing. I opted for a technical demonstration: I would draw the betta fish on her front desk. The image of this fish had arrested me. It was in a large vase. The vase had a plant in it. The fish swam amongst an exposed network of roots. The resulting piece wasn’t my best. I was after all working under unique circumstances. Artists are particular. But I thought it was still pretty good.

“He doesn’t draw people” was Dr. Brady’s only takeaway.

How awful. A critical pan! And so early into my career…

A night like tonight is familiar. I’m supposed to go to a party. There will be many men I don’t know there, including one man I’ve never met in person, but am aware of. He’s very attractive, this man. He’s got black curls and an aquiline nose. I’d like to impress him. My wanting to impress him, I believe, will hurt my chances. My wanting to impress him will make me stilted and uneasy. I believe I will fail. My belief in inevitable failure disappoints me—this belief is surely one of those self-fulfilling prophecies—this belief is indicative of my big problem—my big problem is that I’m too aware—I’m aware that I’m too aware—my awareness of my hyper-awareness only inflames my symptoms, which means I’m only going to get worse as time—Stop it. Cut that out! Snip it with brain-scissors.

Okay.

But what will happen tonight? I suppose I don’t know. Anything could happen. That anything could happen makes me nervous. I picture myself pathetically staying home. I picture going and making a fool of myself. I picture myself standing awkwardly with a drink in one hand and my phone in the other, tooth digging into lip between bouts of forced laughter—I’ll make a bad impression—the man with the black curls and the aquiline nose will think I’m a weirdo—he’ll surely inform his tight-knit community of follicularly gifted men with handsome honkers that I’m no fun—I’m going to be single forever—it will be my fault—a night like tonight is familiar to me—I feel like I’m being pulled, taut and toward—toward another disappointing night—toward another lonely morning—Stop.

You’re doing it again—drawing yourself.

If it makes you feel any better, the horsehair worm in MY brain says many of the same things.

The loose scribbly gracefulness of your line drawings reminded me first of the horror-cartoonist Gahan Wilson, and then of Jules Feiffer, that chronicler of 20th-century anxiety.

I had never tried to picture anxiety before, despite dealing with it for several years! Your description of the worm was really interesting. The hope to remove the offending emotions is so strong. I used to think "if it stays like this I can't go on". But thankfully it changed, I changed, and eventually it became barely noticeable (but the worm comes back here and there when a difficult life circumstance pops up. Then I have to remember all my therapy lessons).😄 Anyway, thank you.